You remind yourself of simple math.

Without the wonder of pulleys and the applied physics behind them, this bow would have a 60-pound draw. Every time you nocked an arrow and pulled it back, you’d have to exert 60 pounds of effort.

Despite the difficult initial pull, that wasn’t the case anymore.

Now, instead of the strain, all you felt was your breath. In your hand was a metal aid; with a click of a switch under your thumb, the latch would open, and the arrow would fly. The process was simple: load, pull, click. Load. Pull. Click. Death.

Shooting with a bow took practice, and it became meditative. People were even making it more accessible — you’d heard of enthusiasts in your city converting an underground bowling alley into an archery range. You mostly remembered the orange glow of sunset behind your parents’ farm, where bales of hay served as your backstop instead of fancy foam.

Lately, you’d become more of a city boy, but you still ventured into the bush now and then. Bringing back a deer meant plentiful meat, and once again, you found your zen.

But in the last few years, your hunting trips had been disturbed by unwelcome visitors. The voices.

High-pitched, saccharine, and utterly lacking self-awareness. Many mornings in the tree stand had been ruined by the cacophony of those blasted Fluffy horses.

This morning was no exception. You’d slung yourself into a maple tree, leaning back to take the weight off your legs. The view was immaculate, and the pond below was a prime spot for deer to drink.

The voices weren’t just annoying — they drove away the game. No deer had patience for Fluffies trying to make “fwends” with the “hown howsie.” They were either trampled or given a wide berth.

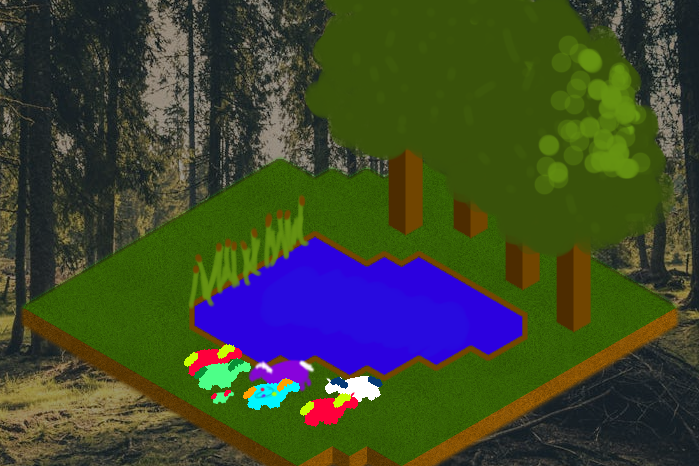

You took a deep breath. The pond’s stillness was broken by the herd of Fluffies that had gathered for water.

It wasn’t just the noise. Fluffy manure — and the remnants clinging to their backsides — had a distinct odor. It felt like an insult that you couldn’t even use their excrement for fertilizer. Everything about Fluffies seemed to take without giving back. The joy of a child on Christmas morning didn’t outweigh the resources spent managing, exterminating, or keeping them from destroying the world.

Your conscience spoke up.

“It’s not their fault.”

You used this to keep yourself in check. You’d heard stories of abusers, exploiters, and murderers — could you even call them murderers? — who seemed unhinged. You weren’t like them. You told yourself that.

Still, you watched the herd below. They’d never crane their necks far enough to see you.

You weren’t sure you liked the term “herd.” It lacked specificity. By your count, there were ten:

- A leader and his partner, both unicorns.

- A breeding pair of earth ponies.

- Another breeding pair: an earth pony and a pegasus.

- Three foals clinging to the pegasus’ back.

- A juvenile colt trotting beside his earth pony father.

You wondered how they’d gotten here. What they’d seen or lost. Maybe this was a fragment of a larger herd, or a mix of ferals and runaways. Maybe none of them had known anything but hardship — hot summers, cold winters, endless hunger, and the constant threat of death. Suddenly, your desire for a three-point buck felt trivial.

The herd distracted you from your thoughts. You couldn’t just ignore them and hope deer would wander to the other side of the pond. Everything about Fluffies repelled sane animals.

Deer could see color, though not as vividly as humans. At least one Fluffy’s coat would trigger their instinct to flee.

Yet, you kept watching. If you were stuck here, you might as well indulge in some light anthropology. YouTube was full of Fluffy videos, with idiots failing to grasp that Fluffies’ sole directive was to seek love and care.

The Fluffies seemed familiar with the pond, moving without caution. The mares played homemakers, debating where to gather bedding. You shifted in your perch, struck by the contrast between their maternal instincts and their stupidity. They had knowledge but no wisdom — a consequence of short lives.

One mare fixated on the water’s prettiness, insisting the herd stay close. The leader’s mate corrected her with a “Wook hewe, dummie,” steering her away from the danger. You shook your head. You were giving them too much credit.

The males discussed “strategy” — mostly food gathering. The colt tagged along, desperate to prove himself. You remembered that feeling: handling your dad’s knife, begging to join a hunt. The hunger for validation.

You centered yourself. Fluffies were always hungry, which meant digestion, which meant poop. Their “latrines” were just holes in the ground. Even a brain stem could grasp that shit smells bad.

But something felt off. This wasn’t real. These were toys — meant for aisles or shelters, not the wild. The more you watched, the more it fell apart. The leader delegated work to his liking, berating an earth pony digging the latrine. Impatient, he threatened physical discipline, then relieved himself before the other could move.

Your fingers strummed the bowstring like a harp. The tension was comforting. You weren’t supposed to draw without releasing, but testing it reassured you it was ready.

There was a balance, like the one you rode with your emotions.

Fluffies didn’t inherently deserve to die. They adapted, like you. They lacked the luxury of morals, which made them ideal toys — malleable to human values.

Toys. That word again.

Strum. Strum. Strum. Sixty pounds of pull.

One arrow could kill a Fluffy. You could justify killing the leader — he was cruel. But would it give back your time, your effort, your family’s patience? No.

Strum. Strum. Strum.

Something wasn’t clicking.

> You are Bluebell, and you’re so happy to have stopped walking. It had been many forevers, and you’d finally be able to enjoy a simple, old-fashioned Fluffpile with your Special Friend, Brook, and the rest of your herd. You had been keeping your new babbehs entertained with the best songs your feeble brain could muster; they seemed to be having fun.

> This round wawa seemed very friendly, and had many nice nummies around it. There were some small buzzie-munstahs around, but not the type that gave your daddeh the biggest booboos you’ve ever seen. Even your herd’s best huggies couldn’t keep him from getting forever sleepies: that was a very hard day.

> You and Brook had been together as long as you can remember, which was probably at least five or six sleepie-times. You had had the best Special Huggies, and after one of the worst nights of your life, you’d finally had biggest poopies and three lovely chirpy babbehs that clung onto your back. They were the future of the herd at this point, since your Smarty Friend and his Special Friend had been a bit too busy to get time for Special Huggies. Your friends Clover and Dasher had a small colt of their own, and despite wanting to immediately have more, your Smarty Friend made sure to keep them from doing so.

> It was a bit mean, but he insisted! Both you and Clover knew that trying to walk a long distance with babbehs was probably bad for them, so eventually you comforted each other and decided to wait until you made a new home.

> Your Smarty Friend’s name was Navy, and his Special Friend was named Cherry. You got along with Cherry for the most part, especially since Navy seemed to give you a bit more nummies once the babbehs had come.

> You craned your abomination of a neck in the direction of Cherry and Clover, who were talking about where to make a fluffpile when it came time for sleepies. Clover really liked how wawa looked, but she was a bit of a dummeh sometimes. Clover was trying her hardest, and eventually convinced her that sleeping beside the wawa wasn’t best for her colt; you’d seen your share of herdmates get a little too comfortable around wawa, and paid the price in forever sleepies.

> If you were sure of one thing, it’s that the wawa was probably the most dangerous thing around here.

Strum. Strum. Strum. Sixty pounds of pull.

You considered how many orphans were too many.

You had an hour before your legs fell asleep, so you entertained hypotheticals — there were three males, three females, one male colt, three indeterminate gender foals. Killing any adult would doom the herd. The leader’s death would collapse discipline. The other two males didn’t really seem to have a lot of initiative or intelligence, and that could play out weird. There’d be an unclaimed mare (the leader’s partner) — you weren’t sure if there would be competition for that mare, or that she’d be driven off.

If the blue mare died, her foals would likely be culled. The others likely wouldn’t have enough milk to feed theirs and hers, and they definitely wouldn’t be so selfless as to give up having their own babies.

If you killed the dumb green mare, the herd would have a surplus of males; her widower might get jealous, selfish or lonely. He’d also be competing against a rapidly-growing colt — would the odd man out kill off his competition?

The more you thought, the less it made sense. Fluffies couldn’t exist without the world allowing it.

Your mind clicked. The world sucked enough.

Strum. Strum. Strum.

You drew an arrow, slow and quiet. You braced yourself, nocked the arrow, and looped your release into your bowstring.

Your favorite part of shooting was the breathing.

Sometimes, when you shot, you felt that initial, large inhale was giving you a gift. As the air cycled in your lungs and your belly inflated, you felt this primal gift get sucked out of the vast nothing that surrounded you every day. That gift gave you sight — the sight to see what your shot would do for you, and your target.

If you were shooting at a deer, that deer would feed you and your family. You would make a contract with that deer in the split-second before you shot — it would know that its life meant something, and its life would continue to help others elongate theirs.

You pulled back on the bowstring as you braced your body. After about 75% of the pull, the pulleys and cams of your bow went to work, and the last portion was surprisingly light to the uninitiated.

That ease was part of the gift. It was the trust the world was putting in you to make the right choice.

Sixty pounds of pull suddenly didn’t feel like that, anymore.

A small pause. A held breath. A target in your sights.

The smallest shift of weight clicks your release open, and you pass on the gift.

The herd would never be the same after this, and would surely not survive the next few days. You would, though. You and your gift.